6 min to read

Turing Incomplete AI

Reflection on the limitations of AI

Turing Incomplete AI

I’ve been seeing a lot of discussion on current limitations of AI, but strangely I haven’t seen much talk about one of the biggest known limitations of current AI models – they are not Turing Complete. I wanted to talk a little bit about this, as it’s something AI enthusiasts and researchers should be aware of. Most of this discussion will be drawn from Ian Goodfellow’s Deep Learning book, which is truly a great resource for learning the basics of deep learning if you are looking for a good textbook.

So what does it mean when we say a Deep Learning model is Turing Complete? By Turing Complete we mean that the model must be able to simulate arbitrary sequential computation with persistent memory. In simpler words, it should be able to simulate any algorithm. Technically there always exist uncomputable algorithms, but for simplicity lets ignore them. A computer is Turing Complete because if you know the steps for a given algorithm, you can always code that set of instructions into a computer to do it. Turing Complete Deep Learning models expand on this by saying, even if you don’t know how to compute a given algorithm, you can train a model to approximate it with enough example inputs and outputs.

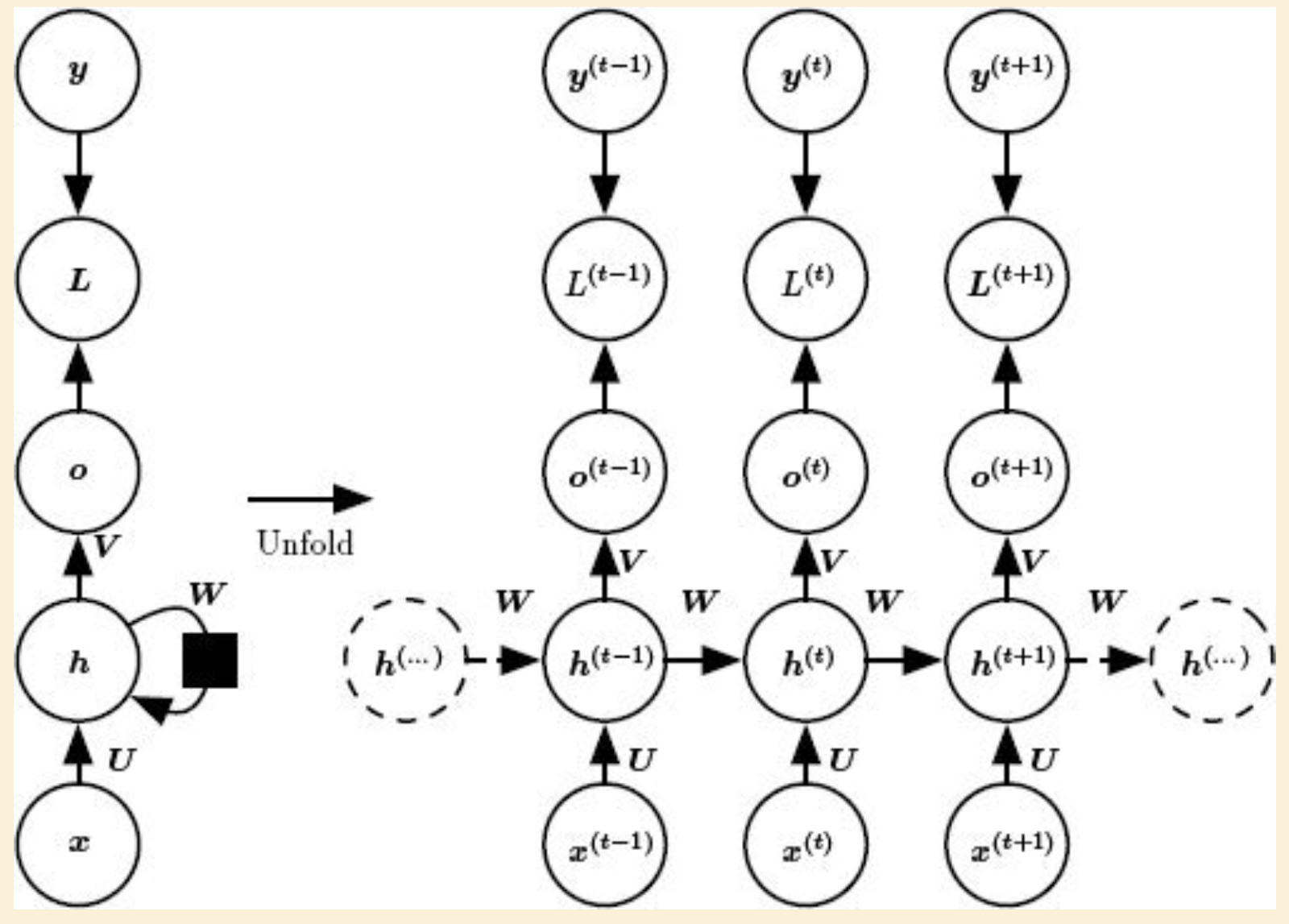

According to Goodfellow’s book, in order for a Deep Learning architecture to be Turing Complete it has to have a certain structure. This model needs to be a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) with structure shown in the figure below. In the diagram, x are the inputs, y is the target, h is the memory, o is the prediction, and L is the loss. U, V, and W are model parameters. Arrows show the direction that information flows. Basically, at each time level the model takes in inputs, updates its memory, spits out an output, then compares the output to the target to find the loss, which it uses to update its parameters. A key to this is that the memory, h, is persistent, meaning that it is a function of not only the inputs, x, but also the memory at the previous time level.

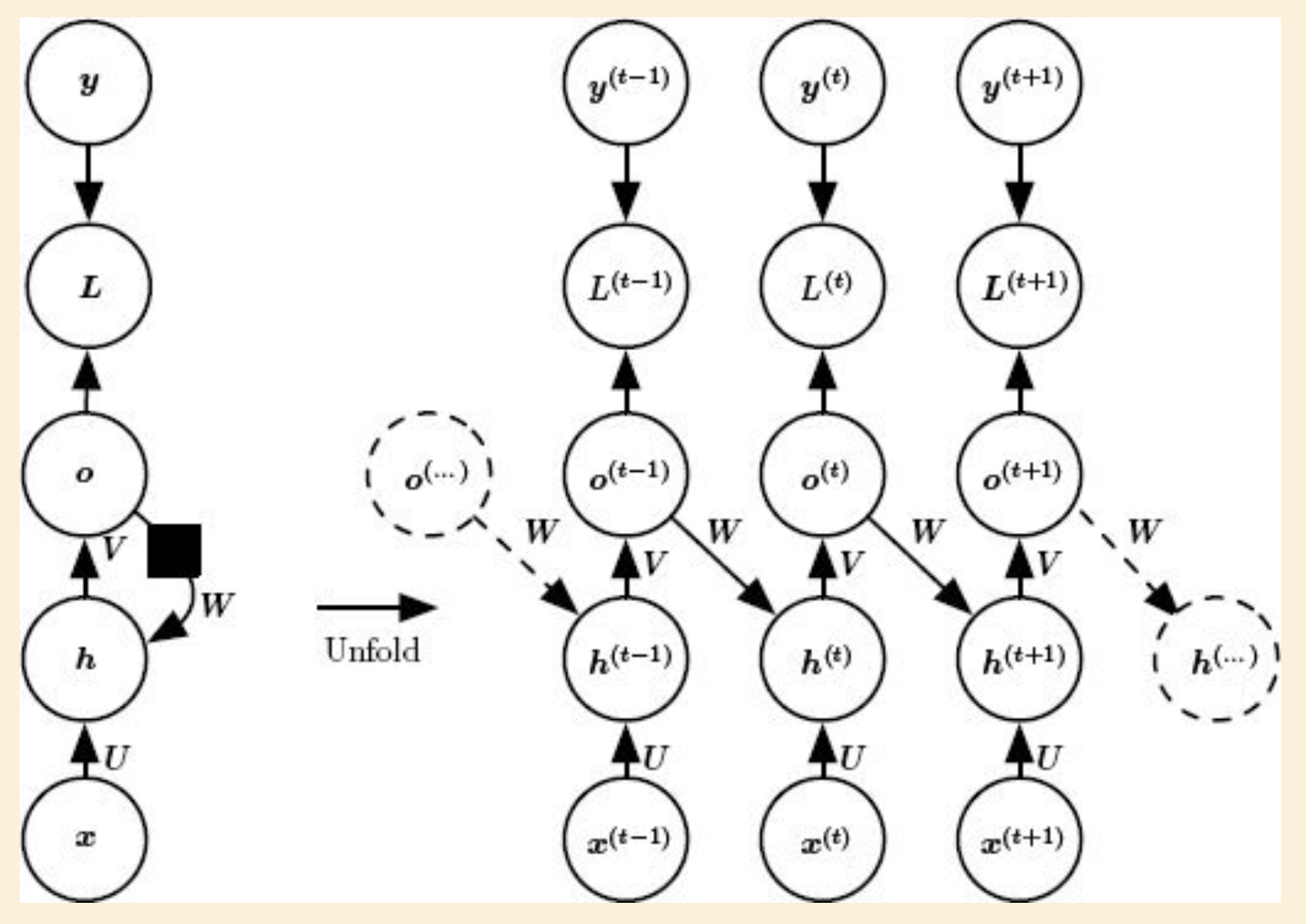

The above figure shows the perfect Turing Complete model, however, this is different from the structure of many LLM models, including ChatGPT. These models use a different structure outlined below. The model still has inputs, x, targets, y, memory, h, outputs, o, and loss, L, however, instead of connecting memory across time levels, they connect outputs of one time level to the memory of the next time level. Effectively, the inputs to the model are the context plus whatever the model just did in the previous time window.

Take a minute to think about what the consequences of this are by thinking of differences between how a human and an AI might write a book report. When humans read a book, we read the book one word at a time, storing a memory of what happened in the previous pages in our brains. When we write a book report, we write it word by word, remembering both what we just read and what we just wrote in our memory. On the other hand, when an AI writes a book report, they start by reading the entire book all at once, fitting the whole book into its context window, then it will write the first word of the report. But after that it completely forgets what it just did, so to write the next word it has to read the entire book all over again plus the one word of the report that it just wrote. It does that over and over again until it finishes the report. Clearly, there is a big difference between how humans operate and how current AI models operate. This is the difference between Turing Complete and Turing Incomplete models.

Models that use the simplified structure end up being really good at doing simple tasks like predicting the next word in a sentence. However, they often fail at more complex tasks, like logic. I’m guessing that a good part of why these models fail at logical tasks comes from the fact that logical deduction is very algorithmic, making inferences at successive steps, and therefore requires Turing Complete architectures.

Why do we use architectures without persistent memory? Goodfellow says it best, “This makes the RNN in this figure less powerful, but it may be easier to train because each time step can be trained in isolation from the others.” Specifically, by eliminating hidden to hidden connections we avoid issues like vanishing gradients, while also allowing the model to train on many examples in parallel. These are huge advantages when you consider how much text a typical LLM is trained on.

There are many ways that people try to overcome the limitations of lacking persistent memory in modern AI, but many of these methods seem like hacks that don’t get to the root of the problem. For example, reasoning models like Deepseek and OpenAI o1 try to hack persistent memory by allowing the model to write notes to itself before making an output. These notes get fed into the context window which might help with making output more reliable, but it doesn’t change the fact that the model will still have to reread the notes at each time step. Similarly RAG models store information in a database, but this is still not a true persistent memory. Additionally, we can also try to make the model more efficient by storing the memory state of context. For example, an AI writing a book report can save the latent representation of the book so that is doesn’t have to reread it, but it would still need to reread the report every time it writes a word. Lastly, the easiest way to fake persistent memory is to just make LLMs with really really big context windows, which seems to be the current strategy. If the context window is big enough, it would be hard to notice when it forgets things.

Overall, the lack of Turing Completeness of modern AI models is something that I think people should be more aware of. Partly because it highlights a clear limit to what AI can do, but partly because it is also a very interesting research direction. A quick Google search shows that there are a number of groups looking at this problem, with solutions like Universal Transformers, that add recurrence, and Neural Turing Machines. I’m interested in seeing if any major improvements in AI reasoning and efficiency come from this research direction.

For those interested in exploring this in greater detail, I recommend these sources.

Ian Goodfellow’s Deep Learning

Siegelmann and Sontag, 1991

Siegelmann and Sontag, 1995

Siegelmann, 1995

Hyotyniemi, 1996

Comments